Go's garbage collector

11 Apr 2020Go’s new [>= v1.5] garbage collector is a concurrent, tri-color, mark-sweep collector, an idea first proposed by Dijkstra in 1978.

Go team has been working intensively on improving the Go’s garbage collector. The whole journey with improvements from 10ms STW pauses every 50ms to two 500μs STW pauses per GC can be found here.

Working extensively on Go, I have been always been intimidated by its performance, so I decided to look under the hood, as to what makes Go so performant and promising, what kind of GC it uses, or how are goroutines multiplexed onto an OS thread, how to profile go programs, how exactly does the go’s runtime work, etc. In this post, we are looking at what and how of Go’s garbage collector.

While browsing through the internet, I came across a lot of appreciation of go’s garbage collector and since I only had an abstract idea as to what are garbage collectors and how they work, I began reading and discovering ans scribbled some notes here about garbage collection.

This blog merely is a scribble of my thoughts and conclusion that I compiled after reading a few blogs related to go’s garbage collector and it’s evolution over time.

Soooo, let’s begin

Hold on tight buddy, it's gonna be a hell of a ride

A little build-up

Go is a value-oriented language in the tradition of C-like systems languages rather than reference-oriented language in the tradition of most managed runtime languages. Value-orientation also helps with foreign function interfaces. It is probably the most important thing that differentiates Go from other GCed languages.

Go is a memory manged language, which means most of the time you don’t have to worry about manual memory management because the runtime does a lot of work for you. However, dynamic memory allocation is not free, and a program’s allocation patterns can substantially affect its performance.

Go binary contains the ENTIRE runtime. And no JIT recompilation.

Because if this the most basic Go binary is generally huge in size.

A brief history of GC’s

Initial garbage collection algorithms were designed for uniprocessor machines and programs that had small heaps, and since CPU and RAM were expensive, users were OK with visible GC pauses. When GC kicked in, your program was stopped until a full mark/sweep of the heap would be done. These types of algorithms do not slow down your program when not collecting and do not add memory overhead.

The problem with simple STW mark/sweep scales very badly, as you add cores and grow your heaps or allocation rates.

Go’s concurrent collector

Go’s current GC is not generational. It just runs a plain old mark/sweep in the background. This has some downsides:

- GC Throughput: More memory your program uses, the more time it takes to free up used memory, and the more time your computer spends doing collection vs useful work.

- Compaction: as there’s no compaction, your program can eventually fragment its heap

- Program throughput: as the GC has to do a lot of work for every cycle, that steals CPU time from the program itself, slowing it down.

- Concurrent mode failure: This occurs when your program generates garbage faster then GC threads can clean it up. In this scenario, the runtime has no option but to stop your program and wait for GC to finish its job! Reference. And to prevent this you need to ensure you have a lot of space to spare, thus adding heap overhead.

Collector Behaviour

Garbage collection occurs concurrently in Go while the program is running.

Enough wait, let’s look at how a collection works.

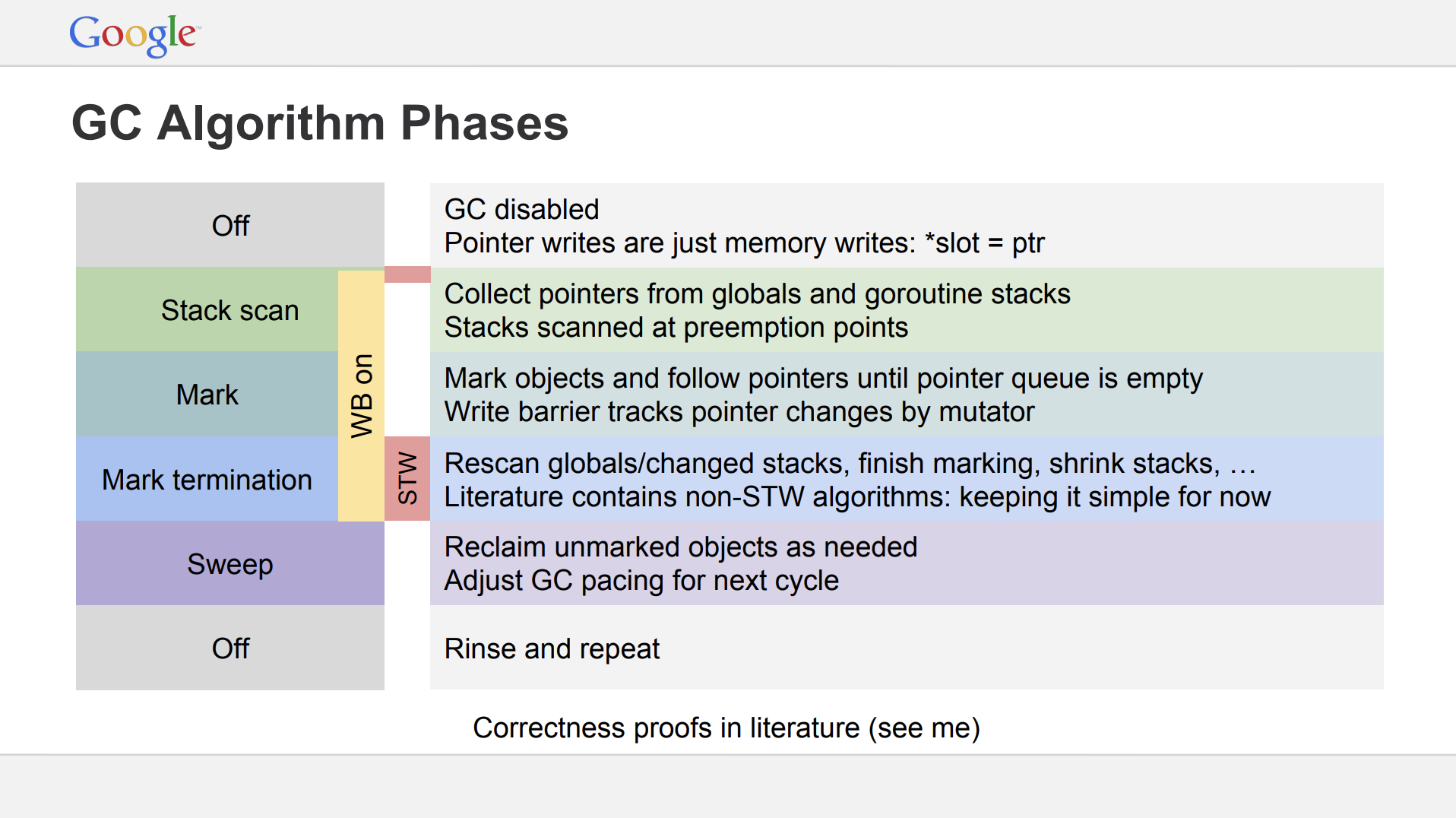

When a collection starts, the collector runs through three phases of work. Two of these phases create Stop The World (STW) latencies and the other phase creates latencies that slow down the throughput of the application.

Mark Setup (STW)

When a collection starts, the first activity that must be performed is turning on the Write Barrier, it allows the collector to maintain data integrity on the heap during a collection since both the collector and application goroutines will be running concurrently. To turn the Write Barrier on, every application goroutine running must be stopped. This activity is usually very quick, within 10 to 30 microseconds on average. That is, as long as the application goroutines are behaving properly.

Suppose four goroutines are running before the GC is about to kick in. Each of these 4 goroutines must be stopped for GC for its work. The only way to do that is for the collector to watch and wait for each goroutine to make a function call. Function calls guarantee the goroutines are at a safe point to be stopped. What happens if one of those goroutines doesn’t make a function call (say it is performing a tight loop operation), then what will happen?

For example, the 4th goroutine was performing the below code

func stubbornGoroutine(numbers []int32) int {

var r int32

for _, v := range numbers {

// some operation to r

}

return r

}

This scenario could stall a garbage collection from starting. Since other processors can’t service any other goroutines while the collector waits. So, goroutines must make function calls in reasonable timeframes.

A goroutine without function calls will not be preempted, and its P will not be released before the end of the task. That will force the “Stop the World” to wait for it.

Marking (Concurrent)

Once the Write Barrier is turned on, the collector commences with the Marking phase.

The first thing the collector does is take 25% of the available CPU capacity for itself. The collector uses Goroutines to do the collection work and needs the same P’s and M’s the application Goroutines use.

The marking phase consists of marking values in heap memory that are still in-use. This work starts by inspecting the stacks for all existing goroutines to find root pointers to heap memory. Then the collector must traverse the heap memory graph from those root pointers.

Mark assist

If the collector determines that it needs to slow down allocations, it will recruit the application Goroutines to assist with the Marking work. This is called a Mark Assist. The amount of time any application Goroutine will be placed in a Mark Assist is proportional to the amount of data it’s adding to heap memory.

Mark Assist helps finish the collection faster.

One goal of the collector is to eliminate the need for Mark Assists. If any given collection ends up requiring a lot of Mark Assist, the collector can start the next garbage collection earlier. This is done in an attempt to reduce the amount of Mark Assist that will be necessary for the next collection.

Mark Termination (STW)

Once the Marking work is done, the next phase is Mark Termination. This is when the Write Barrier is turned off, various clean up tasks are performed, and the next collection goal is calculated. Goroutines that find themselves in a tight loop during the Marking phase can also cause Mark Termination STW latencies to be extended.

Once the collection is finished, every P can be used by the application Goroutines again and the application is back to full throttle.

Sweeping - Concurrent

Another activity happens after a collection is finished called Sweeping. Sweeping is when the memory associated with values in heap memory that were not marked as in-use are reclaimed. This activity occurs when application Goroutines attempt to allocate new values in heap memory. The latency of Sweeping is added to the cost of performing an allocation in heap memory and is not tied to any latencies associated with garbage collection.

How does runtime know when to start a collection?

The collector has a pacing algorithm which determines when to start a collection. Pacing is modeled like a control problem where it is trying to find the right time to trigger a GC cycle so that it hits the target heap size goal. Go’s default pacer will try to trigger a GC cycle every time the heap size doubles. It does this by setting the next heap trigger size during the mark termination phase of the current GC cycle. So after marking all the live memory, it can make the decision to trigger the next GC when the total heap size is 2x what the live set currently is. The 2x value comes from a variable GOGC the runtime uses to set the trigger ratio.

One misconception is thinking that slowing down the pace of the collector is a way to improve performance. The idea being, if you can delay the start of the next collection, then you are delaying the latency it will inflict. Being sympathetic to the collector isn’t about slowing down the pace.

Go 1.5 was released in August 2015 with the new, low-pause, concurrent garbage collector, including an implementation of the pacing algorithm.

Collector latency costs

There are two types of latencies every collection inflicts on your running application.

Stealing of CPU capacity

The effect of this stolen CPU capacity means your application is not running at full throttle during the collection. The application Goroutines are now sharing P’s with the collector’s Goroutines or helping with the collection (Mark Assist).

Amount of STW latency

The second latency that is inflicted is the amount of STW latency that occurs during the collection. The STW time is when no application Goroutines are performing any of their application work. The application is essentially stopped. STW happens twice on every collection.

The way to reduce GC latencies is by identifying and removing unnecessary allocations from your application. Doing this will help the collector in several ways.

- Maintain the smallest heap possible.

- Find an optimal consistent pace.

- Minimize the duration of every collection, STW and Mark Assist.

Two knobs to control the GC

As Rick Hudson said here

We also do not intend to increase the GC API surface. We’ve had almost a decade now and we have two knobs and that feels about right. There is not an application that is important enough for us to add a new flag.

GCPercent

This adjusts how much CPU you want to use and how much memory you want to use. The default is 100 which means that half the heap is dedicated to live memory and half the heap is dedicated to allocation. This can be modified in either direction.

MaxHeap

This lets the programmer set what the maximum heap size should be. Out of memory, OOMs, are tough on Go; temporary spikes in memory usage should be handled by increasing CPU costs, not by aborting. If the GC sees memory pressure it informs the application that it should shed load. Once things are back to normal the GC informs the application that it can go back to its regular load. MaxHeap also provides a lot more flexibility in scheduling. Instead of always being paranoid about how much memory is available the runtime can size the heap up to the MaxHeap.

There is a fairly good description of Go’s GC, in the source code here.

That sums up the Go’s garbage collector. Ofcourse, this didn’t include everything and I may have missed out some points, but I tried to sum up everything I grasped. Below are some really good references that I came across, do have a look!

References

- Getting to Go: The Journey of Go’s Garbage Collector

- The Tail at Scale

- runtime: tight loops should be preemptible

- Go GC: Prioritizing low latency and simplicity

- Why golang garbage-collector not implement Generational and Compact gc?

- Modern garbage collection: A look at the Go GC strategy

- Golang’s Real-time GC in Theory and Practice

- GopherCon 2018 - Allocator Wrestling