Kafka 101

16 Dec 2019Kafka is a distributed, horizontally scalable, partitioned, fault-tolerant, replicated commit log service.

Contents

The What

Kafka is used for building real-time data pipelines and streaming apps. It is horizontally scalable, fault-tolerant, blazing-fast, and runs in production in thousands of companies.

+-------------+

| Log Streams |----|

+-------------+ |

▼ Real-time

+-----+ +-------+ +-----------------+ +------------+

| Web |--------►| | | Spark Streaming | | Dashboards |

+-----+ | |-----►| Flink |---►| Analytics |

| | | Kinesis | | Alerts |

+-----+ | | +-----------------+ +------------+

| App |--------►| Kafka | Batch

+-----+ | | +-------------+ +--------------+

| | | Hadoop | | Archival |

+---------+ | |-----►| S3 |---►| Data Science |

| Data | | | | Spark Batch | | Auditing |

| Streams |----►| | +-------------+ +--------------+

+---------+ +-------+

▲

+--------------+ |

| Service logs |----|

+--------------+

Distributed and fault-tolerant

In a 6-node Kafka cluster, we can have it continue working even if 3 of the nodes are down.

Kafka is a commit log service

A commit log is a persistent ordered data structure which only supports appends. We cannot modify nor delete records from it. It is read from left to right and guarantees item ordering. And that is Kafka’s storage logic (almost).

How it works

Producers (applications) send messages (records) to Kafka node (brokers), and these messages can be consumed by consumers. The records are stored in a topic.

+----------+ +----------+ +----------+

| producer | | producer | | producer |

+----------+ +----------+ +----------+

|__________ | _________|

| | |

▼ ▼ ▼

+---------------+

| kafka cluster |

+---------------+

▲ ▲ ▲

_________| | |_________

| | |

+----------+ +----------+ +----------+

| consumer | | consumer | | consumer |

+----------+ +----------+ +----------+

As topics can get quite big, they get split into partitions of a smaller size for better performance and scalability.

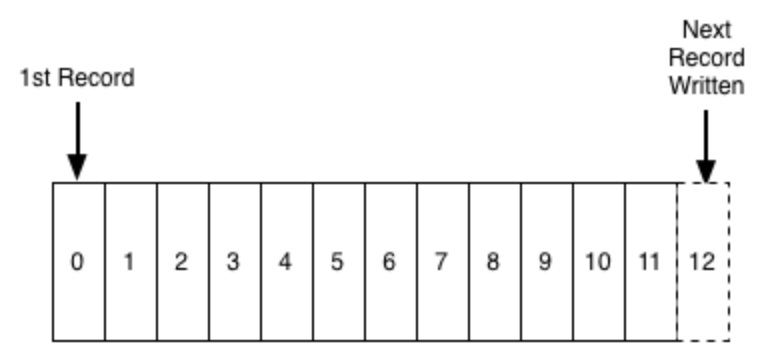

Every partition in a Kafka topic has a write-ahead log where the messages are stored and every message has a unique offset that identifies it’s position in the partition’s log.

And every topic partition in Kafka is replicated n times, where n is the replication factor of the topic. In the event of failure, this allows Kafka to failover to these replicas. Out of the n replicas, one replica is designated as the leader while others are followers. The leader takes the writes from the producer and the followers copy the leader’s log in order.

Kafka guarantees that all messages inside a partition are ordered in the sequence they came in and can be accessed by knowing its offset (similar to an element seek operation in an array knowing its index).

Kafka does not keep track of what records are read by the consumer and delete them but rather stores them for a set amount of time or until some size threshold is met. Consumers poll Kafka for new messages specifying offset they want to read from/at. This allows them to increment/decrement the offset, thus being able to replay and reprocess events.

Producers are generally async, which means the messages are not produced immediately. The message is written into a send buffer for each active partition and transmitted on to the broker by a background thread within the Kafka client library. This makes the operation incredibly fast.

Partitioning

Partitions are the primary mechanism for parallelizing consumption and scaling a topic beyond the throughput limits of a single broker instance.

Consider an example where a topic exists with two partitions and a single consumer (with group id say group_1) is subscribed to this topic. In this scenario, the consumer is assigned control of the both partitions, and consumes messages from both.

When an additional consumer is added to this topic with same group id, Kafka will reallocate one of the partitions from the first to the second consumer. Each consumer instance will then consume from a single partition.

However, the requirements for parallelizing consumption and replaying failed messages do not go away, the responsibility for them is simply transferred from the broker to the client.

Data Storage

Kafka stores data on disk

What on the earth!?

Yes, it is true. Having data ordered in sequential order makes O(1) sequential disk reads which is much faster than random reads from a disk, because linear reads/writes on a disk are fast1 and heavily optimized by the OS, via read-ahead (prefetch large block multiples) and write-behind (group small logical writes into big physical writes) techniques. Also, modern OSes cache the disk in free RAM. This is called page cache.

Read and writes are done in constant time knowing the record id (known as the offset in Kafka terminology). Also, the writes do not block reads or vice versa (as opposed to balanced trees).

This decouples data size completely from the performance. Kafka has the same performance whether we have 10KB or 10TB of data on the servers!

Kafka has a protocol that groups messages together. This allows network requests to reduce overhead, and the server, in turn, persists chunk of messages in one go and consumer fetches large linear chunks at once.

Since Kafka stores messages in a standardized binary format unmodified throughout the whole flow (producer -> broker -> consumer), it can make use of the zero-copy optimization, where the OS copies data from the page cache directly to a socket, bypassing the Kafka broker application completely!

All of these optimizations allow Kafka to deliver messages almost at network speed.

Compression

Kafka is extensively used for high throughput systems (in normal cases even over ~1TB/day), this large volume of data needs to transmitted faster and with minimum bandwidth. By default Kafka, uses plain text messages. This is where compression in Kafka comes into the picture.

Compression2 3 becomes necessary in case of I/O intensive scenario.

Because compression algorithms work well with large data. The more records we have in the batch, the higher the compression ratio we can expect. That is why the producer compresses all the records in the batch together (instead of compressing each record separately).

Kafka supports GZIP, Snappy, LZ4, and ZStandard compression protocols.

Snappy is faster but has a relatively less compression ratio. Gzip achieves a better compression ratio but is more CPU intensive.

Message processing guarantees

In any distributed system, where multiple producers write to messaging system over network, which persists these messages, in multiple locations for redundancy, and one or more consumers poll the messaging system over the network, receive batches of new messages and perform some action on these messages, we need some message processing guarantees, which falls under these categories:

- No guarantee -> consumer may process message once, multiple times or never!

- At most once -> consumer processes message exactly once or never!

- At least once -> consumer processes messages once but may process the same message twice!

- Exactly once -> strongest consistency, consumer processes messages ONLY once

In an ideal case, Exactly once should always be the case, but in real-world, some problems may occur, like, consumer process could run out of memory or crash while writing to a downstream database, broker could run out of disk space, a network partition may form between ZooKeeper instances, a timeout could occur publishing messages to Kafka and we could end up having any of the other three.

No guarantee

enable.auto.commit=true +----------+

+----------+ |------►| Database |

+-------+ | | | +----------+

| kafka |-----►| Consumer |-----| async

+-------+ | | | +----------------+

+----------+ |------►| Offset storage |

+----------------+

The consumer has enable.auto.commit=true, so for each batch, we asynchronously process and save progress to offset storage. If we save the messages to the database and then the application crashes before the progress is saved, we will reprocess those messages again the next run and save them twice. If progress is saved before the results being saved to the database, then the program crashes, these messages will not be reprocessed in the next run meaning we have data loss.

At most once guarantee

This means consumer processes message exactly once or not at all.

If the producer does not retry when an ack times out or returns an error, then the message might end up not being written to the Kafka topic, and hence not delivered to the consumer. In most cases, it will be, but to avoid the possibility of duplication, we accept that sometimes messages will not get through, thus the at most once (also known as “best-effort” semantics).

At least once guarantee

If the producer receives an acknowledgment from the Kafka broker, it means that the message has been written exactly once to the Kafka topic. However, if a producer ack times out or receives an error, it might retry sending the message assuming that the message was not written to the Kafka topic. If the broker had failed right before it sent the ack but after the message was successfully written to the Kafka topic, this retry leads to the message being written twice and hence delivered more than once to the end consumer.

Suppose we had enable.auto.commit=false on the consumer side and the consumer maintains its offset (say in a Redis). Now, the consumer has read a batch and during processing, it crashes, but has already processed half of the batch and saved the results. Because consume crashed, the offset progress was never saved, and thus on restart it reads the batch again and thus duplicating the first half of the batch!

enable.auto.commit=false +----------+

+----------+ |------►| Database |

+-------+ | | 1st +----------+

| kafka |-----►| Consumer |-----|

+-------+ | | 2nd +----------------+

+----------+ |--X---►| Offset storage |

Progess +----------------+

not saved

Since in this semantic we always have the message (may it be duplicated) this is easily achievable and used mostly.

Exactly once guarantee

It requires strong cooperation between the messaging system itself and the application producing and consuming the messages.

Using Transactions in Kafka and idempotent writes we can achieve exactly-once semantics 5.

The Controller Broker

In a distributed environment, if something happens (that affects the nodes), the rest of the nodes must react in an organized way, which means there should be someone that instructs the nodes what to do in event of a failure. Here is where, Controller Broker comes into the picture.

The controller is a normal broker (leads partitions, has writes and reads going through it and replicates data), with some extra responsibility of keeping track of nodes in the cluster and handling nodes that leave, join or fail, including rebalancing partitions and assigning new partition leaders.

A Kafka cluster always has exactly ONE controller broker.

A Controller is a broker that reacts to the event of another broker failing. It gets notified from a ZooKeeper Watch. A ZooKeeper Watch is a subscription to some data in ZooKeeper, when said data changes, ZooKeeper will notify its subscribers. These watches are crucial to Kafka since they serve as input for the Controller.

Scenarios

When a node leaves a cluster

Consider a scenario, where a node becomes unavailable either due to a failure or shutdown, the partitions of which it was the leader of will become unavailable, and since clients only read from/write to partition leaders, the cluster needs to quickly find a substitute leader.

Since every Kafka node sends a heartbeat to ZooKeeper to keep its session alive, so when a broker goes down, its session expires. The controller gets notified and decides which node should become leaders of affected partitions and then informs every associated broker that it should either become a leader of the partition or start replicating from the new leader.

When a node rejoins the cluster

When a node becomes unavailable, some of the remaining nodes become the leader of more partition than they were before, this degrades the performance and health of the cluster as it increases the load on individual brokers.

Kafka assumes that the original leader assignment (when every node was alive) is the optimal one that results in the best-balanced cluster. These are the called preferred leaders (the broker nodes which were the original leaders for their partitions).

Kafka also supports rack-aware leader election where it tries to position partition leaders and followers on different racks to increase fault-tolerance against rack failures.

The most common broker failures are transient, they recover after a while so the metadata associated with the broker is not deleted. When a broker joins the cluster, the controller checks for broker id check if there are partitions that exist on this broker. If there are, the controller then notifies both new and existing brokers of the change. The new broker starts replicating messages from the existing leaders. Since the controller knows the past partition of the newly joined broker and also knows of which it was the leader of, the controller tries to give leadership back to the broker, but because that the rejoined node cannot immediately reclaim its past leadership, it cannot be made the leader of the partition right away!

The newly joined brokers can become eligible to be leaders when they are in-sync with the current leader (Partition leaders themselves are responsible for keeping track of which broker is in-sync and which isn’t), so, if the current leader crashes, the eligible broker takes its place. These in-sync brokers are called in-sync replicas. Kafka’s availability and durability guarantees rely on data replication, so it is extremely important to have a sufficient amount of in-sync replicas.

An edge case can occur where all in-sync replicas and the leader have died4, so an out of sync replica becomes the new partition leader. More on is-sync replicas can be read here.

What happens if the controller broker dies!? (Split-Brain)

If a controller broker dies, the cluster needs to elect a new controller as soon as possible else cluster health can deteriorate quickly!

Electing a new controller is done via a race (the first broker that creates the /controller znode first becomes the new controller broker! Every broker receives a notification that this znode was created and now knows who the latest leader is), but generally the original controller never really dies, it just becomes unavailable for some time (maybe due to GC pause) and then comes back online thinking it is still the controller, this can make things difficult. Since, the cluster has moved on and elected a new controller, so the old controllers now become a zombie controller.

When the old controller comes back online, nothing has changed through its eyes, it is still the controller! We now have two controllers, giving out commands in parallel which can lead to serious inconsistencies. This is solved by assigning a monotonically increasing number - epoch number, stored on ZooKeeper (it is highly consistent). When a controller is elected, it is assigned a higher epoch number and thus even if an old controller rejoins the cluster, the one with the higher epoch would still be the controller.

Consumer groups

Starting from version 0.8.2.0, the offsets committed by the consumers aren’t saved in ZooKeeper but on a partitioned, replicated and compacted topic named __consumer_offsets, which is hosted on the Kafka brokers in the cluster. The broker sends a successful offset commit response to the consumer only after all the replicas of the offsets topic receive the offsets. In case the offsets fail to replicate within a configurable timeout, the offset commit will fail and the consumer may retry the commit after backing off.

+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+

Partition 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | <----- Producer

+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+---+

| |

| |

▼ ▼

Consumer Group A Consumer Group B

To use this mechanism consumers either enable automatic periodic commitment of offsets back to Kafka by setting the configuration flag enable.auto.commit=true or by making an explicit call to commit the offsets.

Every consumer in a group is mapped to a single partition to avoid reading the same message twice.

If consumer group count exceeds the partition count, then the extra consumers remain idle. Kafka can use idle consumers for failover. If there are more partitions than consumer groups, then some consumers will read from more than one partition.

An example where consumer explicitly commits offset

// read offset range

OffsetRange[] offsetRanges = ((HasOffsetRanges) rdd.rdd()).offsetRanges();

// do something with rdd

// commit the offsets to consumer group

((CanCommitOffsets) stream.inputDStream()).commitAsync(offsetRanges);

commitAsync vs commitSync

commitAsync is an asynchronous call and will not block. Any errors encountered are either passed to the callback (if provided) or discarded.

commitSync is synchronous commit and will block until either the commit succeeds or an unrecoverable error is encountered (in which case it is thrown to the caller).

High availability

Kafka is designed around horizontally scalable clusters in which all broker instances accept and distribute messages at the same time.

This brings us back to the now-familiar performance versus reliability trade-off. Replication comes at the cost of additional time waiting for acknowledgments from followers; although as it is performed in parallel, replication to a minimum of three nodes has similar performance as that of two (ignoring the increased network bandwidth usage).

Using this replication scheme, Kafka cleverly avoids the need to ensure that every message is physically written to disk via a sync() operation. Each message sent by a producer will be written to the partition’s log (a write to a file is initially performed into an operating system buffer). If that message is replicated to another Kafka instance and resides in its memory, loss of the leader does not mean that the message itself was lost the insync replica can take over.

Avoiding the need to sync() means that Kafka can accept messages at the rate at which it can write into memory. Conversely, the longer it can avoid flushing its memory to disk, the better. This use of memory means that a single Kafka instance can easily operate at speeds many thousands of times faster than a traditional message broker.

Kafka can also be configured to sync() batches of messages. As everything in Kafka is geared around batching, this actually performs quite well for many use cases and is a useful tool for users that require very strong guarantees. Much of Kafka’s raw performance comes from messages that are sent to the broker as batches, and from having those messages read from the broker in sequential blocks via zero-copy. The latter is a big win from a performance and resource perspective, and is only possible due to the use of the underlying journal data structure, which is laid out per partition.

Much higher performance is possible across a Kafka cluster than through the use of a single Kafka broker, as a topic’s partitions may be horizontally scaled over many separate machines.

Security

In a standard Kafka setup, any user or application can write any messages to any topic, as well as read data from any topics.

By default, there is no encryption, authentication, or ACLs configured. Any client can communicate to Kafka brokers via the PLAINTEXT port.

There is a need to protect user/confidential information, this is where Kafka security comes into play.

Kafka Security has three components:

Encryption of data in-flight using SSL / TLS

Since our message travels across the internet in plaintext, any routers can read the information (MITM attack). Encryption solves this problem.

With encryption using SSL, data is encrypted and securely transmitted over the network and can only be read by the valid consumer. This encryption comes at a cost: CPU is now leveraged for both the Kafka Clients and the Kafka Brokers to encrypt and decrypt packets. SSL Security comes at the cost of performance, but it’s low to negligible.

Encryption is only in-flight and the data still sits un-encrypted on the broker’s disk.

Authentication using SSL or SASL

SSL Auth is leveraging a capability from SSL called two ways of authentication. The idea is to also issue certificates to clients, signed by a certificate authority, which will allow Kafka brokers to verify the identity of the clients.

SASL stands for Simple Authorization Service Layer. The idea is that the authentication mechanism is separated from the Kafka protocol.

Authorization using ACLs

Once the Kafka clients are authenticated, Kafka needs to be able to decide what they can and cannot do. This is where Authorization comes in, controlled by Access Control Lists (ACLs).

ACLs are great because they can help prevent disasters, for example, consider a topic that needs to be writeable from only a subset of clients or hosts. We want to prevent our average user from writing anything to these topics, hence preventing any data corruption or deserialization errors. ACLs are also great if we have some sensitive data and we need to prove to regulators that only certain applications or users can access that data.

More on Kafka Security here.

Rack Awareness

Machines in data center are sometimes grouped in racks. Racks provide isolation as each rack may be in a different physical location and has its own power source. When resources are properly replicated across racks, it provides fault tolerance in that if a rack goes down, the remaining racks can continue to serve traffic.

In Kafka, if there are more than one replica for a partition, it would be nice to have replicas placed in as many different racks as possible so that the partition can continue to function if a rack goes down. In addition, it makes maintenance of Kafka cluster easier as you can take down the whole rack at a time.

This was implemented in Kafka 0.10.0.0. More details can be found here.

Furthur Reading

- Difference between sequential write and random write

- End-to-end Batch Compression

- Squeezing the firehose: getting the most from Kafka compression

- Unclean leader election: What if they all die?

Extensive reading

- Kafka Official documentation

- Kafka Definite Guide

- The Log: What every software engineer should know about real-time data’s unifying abstraction

- How Kafka’s Consumer Auto Commit Configuration Can Lead to Potential Duplication or Data Loss

- Exactly Once Delivery and Transactional Messaging in Kafka

- Enabling Exactly-Once in Kafka Streams

- Processing guarantees in Kafka

- A realistic distributed storage system: the rack model